In September 2004, New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino, then 15, tried out for a reality show. She and her parents were at a mall in Houston when they noticed a booth advertising a casting call, and her dad offered her $20 to audition, as a joke. Three months later, Tolentino was on a plane to the Caribbean to appear in Girls v. Boys: Puerto Rico—which, it should surprise no one, involved two teams of teenagers competing against each other in various challenges while living together in a house brimming with hormones and low-stakes drama.

At the time, reality TV was just beginning its sprawl into every corner of consciousness, and almost all traces of Girls v. Boys: Puerto Rico have since disappeared from not just television but the internet (though it is possible to find one picture of the cast standing arm in arm on the beach, with Tolentino sporting a crop top and a winning grin). It would be easy to dismiss the show as just so much detritus from the new millennium, or simply an early harbinger of what was to come.

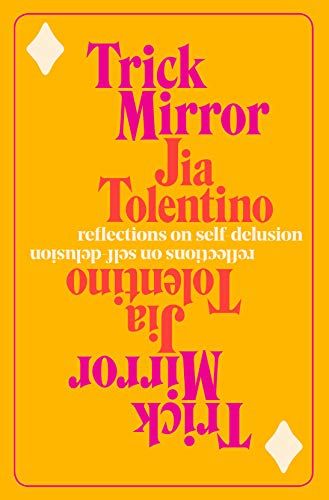

Instead, Tolentino, in an essay from her debut collection, Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion (out August 6), tells a story about her experience with so much depth it practically rips open a portal. Using language that often conjures a Technicolor vividness, it is about how our identities have come to be shaped by algorithms and our sense of reality distorted; about complicity, performance, self-surveillance, and how selfhood itself is a complex, ever-shifting concept. The book includes nine original pieces—about half are personal memoir, while the rest are social criticism—and in all of them, over and over, Tolentino lays out a satisfyingly perceptive insight only to push past it, asking how she might be using it to obscure something else. At one point, in the essay about Girls v. Boys, she writes that rewatching her show felt similar to scrolling through Twitter, “thinking on the one hand, Where are we underneath all of this arbitrary self-importance? And on the other: Aren’t we all exactly as we seem?”

That all this observation unspools from a forgettable early-aughts reality show feels almost like an act of transmutation, as if someone used a bag of Doritos and a bottle of Snapple to produce a multicourse feast. But this is also what has come to be expected from Tolentino during her rapid rise through the media world.

“What is Jia now, 30?” asks David Remnick, the editor-in-chief of the New Yorker, where Tolentino has been a staff writer since 2016. “I mean, God Almighty, I didn’t know how to tie my shoelaces when I was 30. You look at Joan Didion when she was young—suddenly there was this voice that seemed new and distinct and was talking straight at you. Jia’s a very different sort of writer in terms of temperament, but the effect is similarly startling and fresh.”

At the New Yorker, Tolentino’s interests have been omnivorous—she’s covered, among other things, the Westminster Dog Show, abortion rights, the lawyer Gloria Allred, Ovid, and the Cosby trial—and her writing often goes viral. A piece she wrote about the Fyre Festival resulted in her appearance as a talking head in Hulu’s documentary on the event; a feature she wrote about the e-cigarette company Juul led to her being asked to be a panelist at a Congressional briefing on vaping. Routinely, she’ll pull at what appears to be a disparate thread and show it to be part of a vast web in which we are all entangled. She has also proven uniquely able to take up a popular artifact, like weighted blankets or the Pixar movie Coco, and, in exploring her own response, convey the confusion and anguish many Americans feel about the state of our country. “It makes some of the noise fade away, just to hear it through her voice,” says Puja Patel, the editor-in-chief of Pitchfork and a longtime friend. (This has occasionally made Tolentino a target—she recently tweeted a screenshot of an email suggesting she deserved to get anal cancer.)

What can seem contradictory is that while her writing is obviously informed by a searing intelligence, when she appears in it, it’s often as a blank-brained stoner speaking in slang. In the Juul piece, for example, she asks a student in a college library who’s holding an e-cigarette, “Can I…maybe hit it?” (She does.) Similarly, she writes extensively about her own capacity for delusion, but comes across as unusually undeluded. In the essay about Girls v. Boys, a few pages after writing that she auditioned for the show on a whim, she adds, “I like this story better than the alternative, and equally accurate one, which is that I’ve always felt that I was special and acted accordingly. It’s true that I ended up on reality TV by chance. It’s also true that I signed up enthusiastically, felt almost fated to do it. I needed my dad’s twenty dollars not as motivation but as cover for my motivation.”

Tolentino often says she tries to write strong arguments with no conclusions. Instead, many of her endings serve almost as refractions, tilting the story just enough that a new layer appears. The last few paragraphs of her reality TV piece, for example, reference an interview she did with one of her castmates, who says that everyone on the show wanted to be famous, except for Tolentino. “You were the only one who was really not interested,” he continues. “You said you would only ever want to be famous for a reason. You were like, ‘I don’t want to get famous for this bullshit. I want to get famous for writing a book.’”

Today Tolentino lives in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, with her longtime boyfriend, Andrew Daley, an architect, and their dog, Luna, an undocile but good-natured 90-pound mutt whom Tolentino described on The New Yorker Radio Hour as both “the best thing about my life” and “objectively a really bad dog.” In publicity shots of Tolentino, Luna often appears next to her, looking endearingly unhinged. Their home is a small space a half-block from the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, with a door leading to an overgrown backyard in which they used to throw parties until neighbors began leaving what one friend described as “ransom-style notes.” On the day I visit in May, Tolentino, who’s wearing a snakeskin miniskirt and a pink tie-dyed T-shirt, has made coconut cookies that sit in a neat pile on the coffee table in the living room/dining room/kitchen, which is full but not cluttered, with bookshelves in every area they could feasibly fit, and a long table with a laptop and a desktop at one end that also serves as Tolentino’s office (and which they use occasionally for beer pong). On the brick wall behind it is a sign that reads “Drug-Free School Zone” alongside a faithful reproduction Tolentino made of “Monkey Jesus,” the Spanish fresco that became an internet phenomenon after a botched restoration attempt.

Tolentino herself has a buoyant personality, bleached hair whose color she once described as “champagne cocker spaniel,” and a voice just gravelly enough to be sultry. (She has few inhibitions about pursuing her sideline enthusiasms and has occasionally done voice-over work—she narrated a recent commercial for Square, the electronic payment system, and she can be heard explaining how to squeeze the most juice out of a lemon in a 2015 Lifehacker YouTube video.) She’s also enthusiastic about wide-ranging bits of pop culture (lately this includes Lana Del Rey’s cover of Sublime’s “Doin’ Time,” the 1999 mockumentary Drop Dead Gorgeous, and Ocean Vuong’s wrenching novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous) and a lifelong insomniac.

She and Daley seem, in many ways, to be compatible opposites. He doesn’t read much, whereas Tolentino has compared her literary consumption to that of an industrial vacuum. He loves children to the extent that he volunteered at a day care in college; until recently Tolentino described her IUD as her most prized possession. (In June, she tweeted that she’d removed it.) She’s also “extremely online,” as Daley puts it, whereas he has no social media and keeps up with her posts on Twitter, where she has 101,000 followers, by bookmarking her page.

There is a mythology that has grown up around Tolentino, and one rumor circulating is that her work doesn’t require any editing—the friend who told me this a few months back mentioned it in a hushed, almost horrified tone. When I asked her editor at the New Yorker, David Haglund, whether it was true, he said that it varies from piece to piece, but then confirmed another rumor about her, which is that she’s never missed a deadline, at least not with him. “That’s the really upsetting one,” he says. “I think she turned her book in on time, too.” (“She did,” says her literary agent, Amy Williams. “Of course she did.”)

Being around Tolentino, it can be hard to understand how the different parts of her personality fit together. There’s the person who, when expressing her ideas, speaks with such urgency it’s as if her mouth can’t keep up with her thoughts. Then there’s the person who, her legs tucked up underneath her on the sofa, tells me she smokes enough weed that now she sometimes forgets to smoke. “I used to have a sign up that was like, ‘Do you need to smoke weed?’ ” she says. “I’ll go a week and be like, ‘Wait! Weed’s been here this whole time?’” Neither of these aspects seem false. They just don’t often coexist in a single person.

The questions of which sides of her personality are real and which are contrived, which of the stories she tells are trustworthy and which are self-serving, are ones Tolentino herself asks routinely. And one could argue that her awareness of our ability to deceive ourselves is exactly what makes her a clear-eyed observer of this moment. We live at a time, after all, filled with deep fakes and alternative facts, when reality itself shimmers with illusion and many long-standing assumptions no longer seem logical. “It’s hard to imagine anyone putting a pin into what’s going on,” Williams says. “There are no answers. If I’m going to trust anyone, it’s someone who’s doubting her own assertions.” Instead of offering more answers, Tolentino simply tries to chronicle her confusion with clarity, then questions that clarity, too. In the introduction to Trick Mirror, she explains that she writes in order to feel less confused, then continues, “It’s exactly this habit—or compulsion—that makes me suspect I am fooling myself. If I were, in fact, the calm person who shows up on paper, why would I always need to hammer out a narrative that gets me there?”

Tolentino often presents herself, in life and in her work, as both enthusiastic convert and impartial critic. This past March, for example, in a New Yorker feature about the activewear brand Outdoor Voices, she writes that, as research, she decided to adopt OV’s slogan, “Doing Things,” as a mind-set and regularly pursue exercise she enjoyed. Working out so much put her in a “terrific, if conflicted, mood,” she writes. Then she adds, “Am I taking care of myself, doing sun salutations in my motivational crop top, or am I running survival drills for life under an advanced capitalist economy? The answer, I’m sure, is both.” Two months later, Tolentino went hiking in Utah with a friend, and posted a series of photos on Instagram in which she’s wearing OV—one person commented, “#doingthings.” “I was like, ‘Fuck me,’ ” Tolentino says. As for her experience of the trip, “You feel so lucky that this was colonized by Europeans, you know what I mean?” she says. “I don’t belong there. And the only reason I’m able to be there was because of this legacy of intense cruelty, right? I feel like one of the juxtapositions [of this era] is that what joy we have is predicated on being one of the lucky ones. And always at someone’s expense. What kind of joy is possible without ever forgetting that? I’ve been trying to figure out what kind of hope can be predicated on fatalism.”

While Tolentino was growing up in Houston, almost every aspect of her childhood seems to have been calibrated to foster in her an ability to be comfortable in any environment—“fully, willingly present,” as she describes it—but also able to pick it apart. In the mid-1980s, her parents emigrated from the Philippines to Toronto, where she was born; they moved to Houston when she was four (she also has a younger brother). There, the family joined an evangelical megachurch that ran a small private school, which Tolentino attended (as did, years earlier, Ted Cruz), even though her parents were less stringently religious than those of many of her peers. “They wanted me to go to a good school,” she says. “It just happened to teach creationism.” Tolentino also began first grade early, making her about two years younger than her classmates, and the school was mostly white and wealthy, whereas for about half her time there, she was on scholarship. “As long as I can remember, I was completely different from everyone around me,” she says. “Yet because of my temperament, I was completely at home.”

A cheerleader and the salutatorian, Tolentino rebelled, slightly. She appeared three times in Fiddler on the Roof, a musical she loves, but also thought it was funny, in the mournful ending, to lie down on the floor and pretend to be dramatically giving birth. “Everyone knew Jia was the smartest person in our class by a million miles,” says Robert Doty, a friend who was in her grade. “And she was always a good student, so the teachers liked her, but they hated that they couldn’t control her.” In an essay from Trick Mirror that somehow manages to braid together her school, religion, the drug Ecstasy, and a type of remixed Houston hip-hop called “chopped and screwed,” Tolentino recalls that during her graduation speech, she broke from what she’d prepared and made jokes, including one referencing the fact that students referred to the church as “The Repentagon.” But she also writes, “I’ve always been glad that I grew up the way that I did. The Repentagon trained me to feel at ease in odd, insular, extreme environments…and Christianity formed my deepest instincts.” It is, for example, a big part of why the question of how to engage ethically in an ethically compromised world informs so much of her work. “Writing, for her, is a moral act,” Haglund says.

She got into Yale University early admission, but during her senior year of high school, she learned that her parents were facing money problems, and that once she was out of the house she’d have to be financially independent. This was right before she left to film Girls v. Boys: Puerto Rico (she’d convinced her school to let her have three weeks off by saying she hoped to “be a light for Jesus, but on television”). Once she returned to Texas, she applied for and then accepted a full merit scholarship to the University of Virginia.

In college, Tolentino joined a sorority and was an English major. She was also part of an a cappella group called the Virginia Belles—in the evidence that still exists on YouTube, her voice is sweet and slightly throaty. The fact that she is skilled at so many things actually became a joke within the group. Daley went to UVA as well, and initially encountered Tolentino at an a cappella concert. “Someone had put together a video basically making fun of Jia for being supersmart and incredibly talented, but also loving dumb things,” he says. “It was meant to take place 20 years in the future and showed that Jia had cured cancer, and Jia had solved global warming, and Jia had won a Pulitzer Prize.”

“I’ve had the exact same personality since I was three,” Tolentino says. “Like, the exact same.” Her views, however, have changed. While growing up, “I probably considered myself a libertarian,” she says, and she didn’t call herself a feminist until after college. She’s now a progressive who has a whole essay in Trick Mirror about (among other things) how she doesn’t want to get married. She remains able to relate to people who disagree with her, though. “I don’t even want to know how many of the people we graduated with are Trump supporters,” Doty says. “But she found a way to love those people and still does—a lot of them. I think that what Jia fundamentally understands is that human love is messy and weird. And she likes it that way.”

When it comes to getting along with different sorts of people, it likely helps that Tolentino is quick to make herself a punch line, is earnestly into internet memes, and doesn’t often lead with her intelligence. “There is a huge portion of me that is very legitimately stupid,” she says. “If we had met this weekend, when I was at this music festival in Gulf Shores, Alabama, you’d be like, ‘This girl’s a fucking idiot.’” Though her acceptance has limits. At the festival, her friends went to a party where there was an NFL player who asked, as part of a game, what was something every man hates—the answer was “feminists.” “That dude, I’m done with him forever,” Tolentino says. “At the same time, I was partying with him all night.”

After college, Tolentino joined the Peace Corps and intentionally didn’t request a country, hoping to be sent wherever she was needed. She ended up in Kyrgyzstan, which she later described in The Awl as “a post-Soviet, syncretically Muslim, rapidly globalizing country in Central Asia that looks like a combination of Switzerland and the moon.” The experience “flattened me,” she says. A week after she arrived, there was a coup, and she and other volunteers were evacuated to an American air base. Later, in her village, Tolentino was confronted by deep poverty—there was no running water and never enough heat, and she was haunted by the memory of a $27 cocktail she’d once ordered, she wrote in The Billfold, “as I watched my tiny, hungry host siblings divide every meal.” She ended up leaving early, with the program’s encouragement, partially because she broke a few rules, and also because she’d frequently been sexually harassed (bride kidnapping still occasionally occurs in the country, and it didn’t help that Tolentino was sometimes assumed to be Kyrgyz). Doty says she was different when she returned. “There was a seriousness to her,” he says. “I think it made the world more real.”

Tolentino only included a few pages about Kyrgyzstan in the book, partly, she says, because she didn’t take notes while she was there. “It’s hard to be like, ‘Here’s what happened to me today,’ ” she says. “You feel like an asshole.” Still, these passages are memorable. “She writes with such sympathy for the way all of us have to bear up under endless performative demands,” says the writer Gideon Lewis-Kraus, another friend of hers. “But she seems to move between the various performances required of her with such fluidity and ease. When she writes about Kyrgyzstan, that’s one of the rare moments she seems genuinely destabilized.”

Back in the U.S., Tolentino applied to the fiction MFA program at the University of Michigan, received a fellowship, and moved to Ann Arbor with Daley. The first short story she submitted anywhere ended up getting published in the literary journal Carve, winning the 2012 Raymond Carver Contest and being nominated for a Pushcart Prize. But even as many of her classmates focused solely on fiction, Tolentino pitched a series of interviews with adult virgins to The Hairpin, the beloved idiosyncratic, now-defunct women’s site. When Emma Carmichael became its editor-in-chief, she hired Tolentino as a contributing editor and they became close, despite mostly running the site via Google Docs and Gchat. “It was like having a pen pal,” Carmichael says. A year later, they finally hung out in person at SXSW, where they shared an air mattress at an Airbnb mutual friends had rented. “The house was a complete disaster zone,” Carmichael says. “We broke the hot tub.” Patel, who was already close with Carmichael, met Tolentino for the first time at that SXSW, too, and assigned her to write a review of a ScHoolboy Q performance for Spin, where she was editing at the time. “The next day she couldn’t file,” Patel says. It remains the only deadline Tolentino has ever missed.

In 2014, when Carmichael began running Jezebel, she hired Tolentino as deputy editor (she moved to New York from Ann Arbor two days before starting the job), and she rapidly established herself as a writer with almost bewilderingly broad abilities. She could be funny; she could construct pieces that combined reporting with personal history (as she did in a piece covering Rolling Stone’s debacle of an article about rape at UVA); and she could write essays exploring the expectations people have of Jezebel itself, as she did in one titled “No Offense,” which began, “It’s strange to edit a feminist website when almost nothing offends you, because the feminist website is traditionally imagined to run on offense.”

Soon, she was regularly turning down other job offers, in part due to loyalty to Carmichael, who by then was not just her best friend and boss, but had also been involved in a serious car accident in the summer of 2015 that had landed her in the hospital for six weeks, at which point Tolentino had stepped in to run the site. Meanwhile, Gawker Media, the company that owned Jezebel, was embroiled in a lawsuit involving a Hulk Hogan sex tape that ultimately led it to file for bankruptcy. (Tolentino once described the period as “maniacally strange.”) “But I also think she realized it was a time to have fun before she became one of the voices online that people turn to in order to be told how to think,” Carmichael says.

The offer to write for the New Yorker was different, though. “I was like, Yes, absolutely. Are you fucking kidding me?” Tolentino says. She began her new job in July 2016; four months later, Trump was elected. “I felt useless and agitated and confused, like everyone did,” she says. “I was like, ‘What is a way I can feel all these things for a good purpose?’” Her conclusion was to write a book, and she landed a deal that summer while reporting from the Cosby trial, running outside the courtroom to talk to editors.

For the next 18 months, she worked on Trick Mirror most weekends and some weeknights. Early responses have been rapturous. It’s been blurbed by Zadie Smith and Rebecca Solnit, who called Tolentino “the best young essayist at work in the United States.” The starred Kirkus review declared that it positioned Tolentino as “a key voice of her generation,” though she shrugs this off. “I think it’s a subject matter thing,” she says. (“It’s broader than that,” Williams says. “She’s writing about things we all live with.”)

The anal cancer email notwithstanding, the criticism Tolentino receives these days tends to be more muted than when she was at Jezebel, where people sometimes tweeted at her with pictures of her face plastered with dicks. The essay she expects to prompt the most blowback is one in which she argues that being a “difficult woman” has been reframed as an undiluted positive. “The concept has ballooned to something all-encompassing...a tarp of self-delusion that can cover any sin,” she writes, adding, “If you stripped away the sexism, you’d still be left with Kellyanne Conway.”

The piece has the capacity to anger both people on the left and, presumably, Kellyanne Conway and her supporters. It’s also indicative of the way Tolentino’s path through most any subject, no matter how contentious, is her own. “The ways in which our identities position us in the world are complicated,” she tells me. “And we’re in an age where everything is shifting. There has to be writing that is flexible enough to accommodate all these things existing, often at once.”

One concern she had about her essay on Ecstasy and religion was that just putting words to something so central to her identity would leave it unable to further develop. “I worried I was imposing some sort of false structure and would no longer have these overwhelming experiences,” she says. She was relieved, last April, when she went upstate, dropped acid, and discovered this, at least, was not the case. “The message of the day was, Jia, what an idiot you were to even think you were getting to the bottom of anything,” she says. “That essay is just a sliver on the top of this thing that you’ll be thinking about for the rest of your life.”

This article will appear in the September 2019 issue of ELLE.