That balmy gust of summer air often brings with it a flurry of memories: kicking through steaming hot sand at the beach, dropping grill-burnt hot dogs on freshly-laundered clothes, and front crawling to the deep end of swimming pools—the latter of which many Black kids had to watch waist-deep from the shallow.

White men can't jump, and Black men can’t swim—many heard of us heard these phrases growing up. But only one is a culturally-embedded stereotype rooted in racism. Before swimming became the symbol of relaxation and tranquility it is today, municipal swimming pools also served as a reminder of America's fraught racial history. On June 18th, 1964, a 17-year-old Black woman named Mamie Nell Ford, along with six other protesters, staged a "swim-in" at the Monson Motor Lodge pool in St. Augustine, Florida to fight against segregation. Infuriated by the act, motel manager James Brock dumped muriatic acid into the pool of Black activists, resulting in a widely-circulated photo of Ford's visible shock becoming a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement.

But the passage of legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 couldn't prevent the generational impacts of institutionalized racism. Inaccessibility to clean, functioning swimming pools and affordable training continues to persist to this day, forming a major gap between white and Black Americans' swimming ability. If Black people were afforded the same recreational privilege of their white counterparts, there would be more swimmers like Simone Manuel, who was just one out of two Black women on the Olympic swimming team and made history as the first-ever Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal for the United States. Images of Black swimmers fearlessly back-stroking through pools or holding up gold medals would replace the ones of Black kids getting acid thrown on them and "white only" signs hanging outside of private pools.

"We say that joy is an act of resistance, that existing is an act of resistance. Swimming is an act of resistance," Paulana Lamonier, founder of Black People Will Swim, tells ELLE.com. The program was launched in March 2020 when Lamonier—a journalist and former swim coach—grew increasingly frustrated by the bias permeating the swim community. Black People Will Swim takes a four-pronged approach to help swimmers "F.A.C.E" their fears: Fun, Awareness, Community, and Education. Ahead, Lamonier explains how Black People Will Swim aims to dismantle the long-standing myth that Black people can't swim using everything from private swim lessons to haircare classes for protecting Black hair in the water.

How did your relationship with swimming start?

I was about nine when my mom put me in swimming classes at a local swim program in Long Island, NY. But then I forgot everything, and if you don't use it, then you lose it. Then I joined the swim team over at my school, CUNY York College, in 2009. After a year of swimming there, my coach asked me to be the assistant coach for his swim club—where he teaches babies and toddlers how to swim—and then I was like, "Hell yeah." From there, I started working at the Jamaica YMCA [in Queens] and that's where my love for swim grew deeper because I'm working in the community with a whole melting pot of cultures.

While working at the Jamaica YMCA, what were some of the responses you'd hear as to why people chose to swim?

A lot of people chose to swim because this was a fear that they wanted to overcome. This was something that their parents made them do. A lot of kids' parents didn't know how to swim so that trauma was passed down. I had this one girl, she had a really hard time getting in the water—even putting her toes in the water was just a really big deal. Recently, I had a client tell me she was really scared to swim because "you know Black people don't swim, right? Our bones are too dense." And from that moment on, I knew I had to smash these fears. I wanted to create a campaign to smash these fears they have because if you keep saying you can't long enough, you will believe that it's actually true.

What inspired you to launch Black People Will Swim?

Initially, I started it after tweeting that I wanted to teach 30 Black people how to swim this summer. And girl did I get retweets. I created a quick form where people would sign up and I received responses from Miami to Jersey—and mind you, I'm in New York.

So I started with the people that were immediately in Long Island. I started with about 24 people—most of which were Black people and a few were Asian. I don't discriminate. And it got so overwhelming that I actually brought my sister on to start teaching people how to swim.

To put it plainly, representation matters, and I want to showcase that this isn't just a white sport. This isn't just a privileged sport. This is a necessity, this is a life skill, and this is something that racism has prevented Black people from doing for a long time by telling us our bones are too dense. This is why it's important for organizations like Black People Will Swim to defy the odds and smash the stereotype. When I got re-certified to be an instructor last year, there were eight students in class. Out of the eight students, I was one of two Black students and the other woman was someone I already met at the YMCA.

How does race and bias play a role in the deeper meaning behind the myth "Black people can't swim?"

There are a multitude of factors that contribute to that myth. The Jim Crow law played a huge role in that. Then, there's "white flight." As more Black people started coming into neighborhoods in Queens and Brooklyn, white people started moving more out east. White people have access to country clubs and have access to these pools out east, but you don't really see a lot of those in Brooklyn or Queens. For white people, they grew up with pools in their backyard or their parents taught them. Black people didn't have access to those pools swimming so it's not normalized in the community. Also, we can point to intergenerational trauma. People don't realize that trauma is passed down from generation to generation. "I don't swim because my cousin had a drowning incident," or some Black parents, what they like to do is just throw their kids in the water and tell them to figure it out. Lastly, our hair. We know our hair is a huge part of our identity. If we're not being taught how to take care of our hair in the water, guess what? We're going to eliminate the whole thing and just not bother.

Seeing in believing. Representation matters because if I see someone who looks like me, who talks like me, just imagine the impact that it'll have. Just seeing Serena [Williams] and Venus [Williams] killing it on the tennis court. Coco [Guaff]. Naomi [Osaka]. In swimming, we have Cullen Jones and Simone Manuel. Imagine what trophies and medals we can earn in swimming. Those are two well-known Black swimmers, but we need to add more people because Black people do swim.

Your goal with Black People Will Swim was to teach 2020 people how to swim by the end of the year. Obviously COVID delayed plans, but I'm curious to know how far you've come now that we're in the sixth month of the year.

Unfortunately, COVID came early on in the game just as we were picking up steam. The goal is still the same, but we have to push our goal back to December 2021 to be realistic, as we don't want to put anyone's health in jeopardy. Hopefully, we would love to start in September, but if not, we'll keep encouraging people to share their stories. We know that being Black is not monolithic and neither are our experiences. We have a campaign coming up in the works where we are doing a deep dive into Black people and their relationship with water. We're just using the power of storytelling as an alternative.

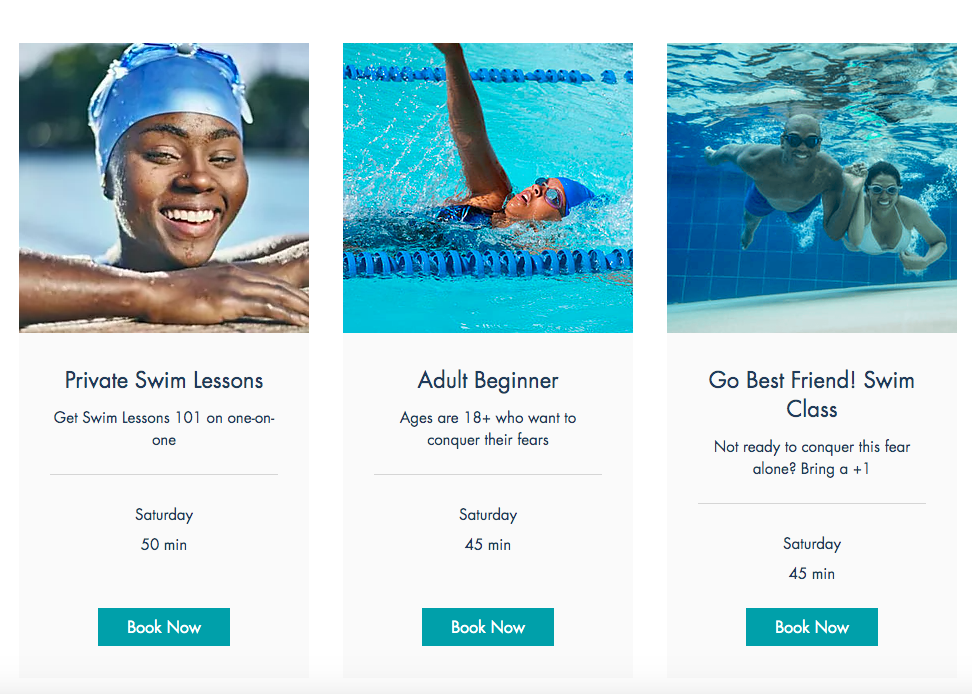

What kind of classes does Black People Will Swim offer?

When you go to our website and sign up, we have so many classes to choose from, which I think is what makes us so important. We have private lessons if you're not ready to do a group class. But then also we have a "Go Best Friend" class that you can bring your best friend (or cousin, or mom, whoever you consider your best friend) to join you so you don't have to conquer this fear by yourself. So far, we have one main location in Brooklyn and we're working on a Long Island location, but that's later in the future.

If you don't know where to get a cap or goggles, we will sell them to you. During the day, we host a haircare class to provide tips and tricks for taking care of your hair while swimming. Plus, you can walk away with some free products and meeting people who have been doing this for a while.

How did you go about choosing the prices?

I've been teaching for 10 years and I've worked at different locations, so I know what's pricey and what's not pricey. I think about the average income for Black communities in Brooklyn. I don't want to charge a crazy expensive price because that what has prevented many from swimming in the first place. But the reason why I'm charging them is to show them that this is an investment for life.

Can you really be too old to learn how to swim?

What I love most about swimming is that it's not like any other contact sports like basketball or football where there is a certain age cap. With swimming, there isn't. For instance, the Harlem Honeys & Bears is a senior synchronized swim team where they're not only dancing in the water, but they're also teaching the kids in their community how to swim. These are people in their 60s, 70s, and 80s, pushing their 80s, swimming for leisure and teaching others. You're never too old to learn something new.